Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, first published in 1764, is widely celebrated as the cornerstone of the Gothic novel genre.

Its subtitle, A Gothic Story, coined the term “Gothic” to describe a new blend of medieval atmosphere and supernatural terror that has echoed through literature, film, art, and even modern goth subculture.

Set in a haunted castle, the novel’s chilling mix of fantastical occurrences and dark medievalism has influenced countless works across genres and media, establishing an aesthetic that remains hauntingly potent today.

A literary revolution

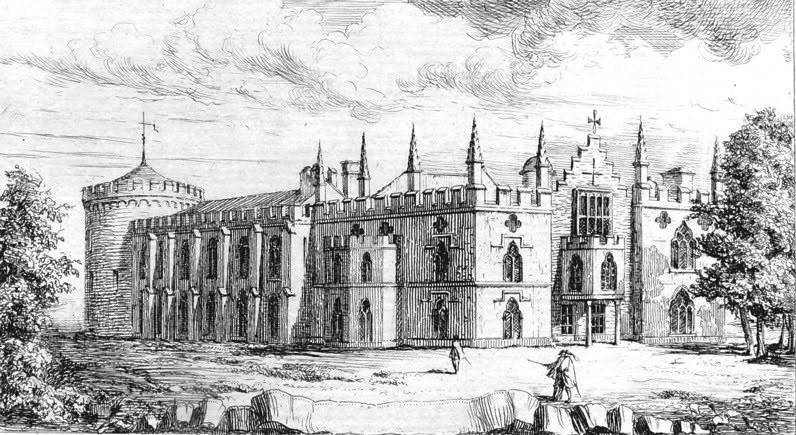

The inspiration for this trailblazing tale is just as intriguing as the novel itself. Walpole claimed that the idea sprang from a vivid nightmare he experienced at his Gothic Revival home, Strawberry Hill House in Twickenham.

The nightmare featured a “gigantic hand in armor,” a haunting image that Walpole masterfully wove into the novel.

His fascination with medieval history and Gothic architecture further enriched the book’s atmosphere. He blended historical influences with his eerie vision to craft a story that was both imaginative and unsettling.

The Castle of Otranto set the stage for a literary revolution. Its success spawned a wave of Gothic fiction that would sweep through the late 18th and early 19th centuries, influencing writers like Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, and Edgar Allan Poe.

These authors embraced and expanded upon Walpole’s Gothic blueprint, introducing readers to haunted mansions, mysterious bloodlines, and tragic heroes grappling with the supernatural.

An air of mystery

Written while Walpole was serving as a Member of Parliament for King’s Lynn, The Castle of Otranto was published under a playful ruse.

The first edition claimed to be a translation of an ancient manuscript from Italy, supposedly written in 1529 by one Onuphrio Muralto and discovered in the library of an old Catholic family in England.

This deception added an air of mystery to the novel, drawing readers into its eerie world as though they were uncovering a forgotten relic of medieval lore.

However, in subsequent editions, Walpole dropped the pseudonym, admitted authorship, and explained his intent: to merge the imaginative freedom of ancient romance with the realism of contemporary novels.

Walpole’s connections to Shakespeare are another fascinating layer of the novel’s rich tapestry.

By doing so, he crafted a hybrid form of storytelling that brought fantasy and realism into an eerie, captivating harmony.

At the heart of Otranto are some of the most iconic tropes of Gothic fiction. Enchanted helmets that crash from the sky, portraits that seem to move, and doors that slam shut by unseen hands all contribute to the novel’s uncanny atmosphere.

These elements became hallmarks of the genre, shaping how subsequent Gothic tales intertwined the supernatural with the mundane.

Thomas Gray, a poet and friend of Walpole, confessed that The Castle of Otranto made readers “cry a little” and left them “afraid to go to bed nights”—a testament to the novel’s enduring ability to thrill and unsettle.

The influence of Shakespeare

Walpole’s connections to Shakespeare are another fascinating layer of the novel’s rich tapestry. In the preface to the second edition, Walpole praises Shakespeare as a genuine original, lauding his imaginative freedom—a quality Walpole sought to emulate in Otranto.

Throughout the novel, Walpole draws explicit parallels to Hamlet, particularly in Manfred’s eerie encounters with ghostly figures, echoing Hamlet’s experience with the spectral. Walpole cleverly taps into the sense of unease and moral ambiguity that Shakespeare explored, crafting a novel that, like Hamlet, asks its audience to confront deep-seated fears about identity, family, and fate.

At the core of The Castle of Otranto lies an exploration of lineage, inheritance, and the dark secrets that can haunt bloodlines.

In this way, the novel mirrors Shakespearean tragedies such as Macbeth and Richard II, where questions of succession and rightful inheritance fuel the characters’ descent into chaos. The incestuous undertones in Otranto, where familial bonds are twisted and violated, add a layer of taboo that heightens the novel’s tension and sense of moral decay.

Yet, Walpole doesn’t confine his novel to pure tragedy. In true Shakespearean fashion, he uses minor characters, particularly servants, to inject moments of comic relief into the story.

This balance of light and dark, humor and horror, was a narrative technique Walpole borrowed from the Bard, adding a depth of tone to his otherwise somber and suspenseful tale.

A template for terror

Although The Castle of Otranto was initially hailed as a masterful, mysterious text, its reception soured after Walpole revealed that the novel was not a discovered relic of the past but a piece of satirical fiction.

Critics dismissed it as frivolous and absurd, unworthy of serious literary merit. However, the novel’s influence was undeniable. Clara Reeve’s The Old English Baron (1777) was written as a direct response to Otranto, aiming to refine Walpole’s blend of fantasy and realism to suit the tastes of the time better.

Perhaps one of the most significant Gothic works to follow Otranto was Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796), a novel that pushed Walpole’s formula to its extreme, indulging in an excess of sensationalism and horror.

Some even regard The Monk as a parody of Otranto, showing how the genre Walpole pioneered could be taken in vastly different directions.

The Castle of Otranto stands as a landmark in literary history, not just for launching the Gothic tradition but also for continuing to invite fresh interpretations and inspire creative works centuries later.

Whether seen as a template for terror or as a satire on medieval romance, Walpole’s novel remains a haunting reflection of our deepest fears and the dark corners of human imagination.

Leave a comment