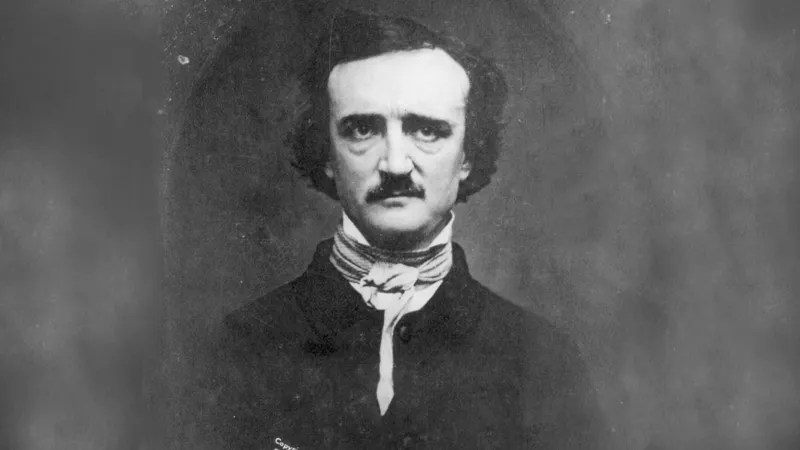

Sitting in the dimly lit basement of my grandmother’s South Philadelphia rowhome, my cousin Michael and I sat spellbound as she read aloud from “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” We were just pre-teens then, often spending weekends at her house, where she introduced us to the eerie world of Edgar Allan Poe through an anthology of his stories.

My grandmother was no ordinary grandma—she was the cool one, the artist. She painted vivid images, whether Japanese geishas or the bold lines of a Spider-Man comic book cover. Her creative spirit was magnetic, and we gravitated toward it.

She lived with my great-grandmother, a quintessential Italian-American matriarch who filled the house with the aromas of simmering gravy, pasta, and meatballs every Sunday. She took great pride in making sure the family was well-fed. Together, they made their modest South Philly home a place of comfort, creativity, and warmth—memories I cherish deeply.

One of the reasons we spent so much time there, aside from our love for them, was that my grandmother, Marianne, was in poor health. A lifelong smoker, she had developed emphysema, and her condition worsened over time. Even as her health declined, she remained a larger-than-life presence in our world.

Michael and I, perhaps aware on some level that our time with her was limited, made a point to be there every weekend, even when we could’ve been with friends. We couldn’t pass up those hours with her, the storytelling, and the laughter.

Her health continued to deteriorate, and she eventually passed away during my sophomore year of college. It was a loss that left a deep imprint on me, but those precious weekends spent with her are some of the most valuable moments of my childhood.

Years later, as I navigated my own struggles—getting sober from drugs and alcohol—I found myself seeking guidance from a spiritual director named Mick at a Catholic monastery. He was a gentle and kind soul, someone who listened intently. One Saturday morning, I told him about those times when my grandmother would read Poe to us.

“That’s a bit morbid,” Mick said, raising an eyebrow.

I could tell his words had no judgment, and I wasn’t offended. In fact, I felt an odd sense of pride. Sure, it was a little morbid, but it was also cool in its own way.

That conversation stuck with me, and as I’ve grown older, I’ve realized how much those early days of listening to Poe have shaped my interests. I wasn’t immediately drawn to horror as a genre, but it has always pulled me in like a magnet. As I inch closer to middle age, I spend much of my time writing spooky fiction, devouring classic and modern horror, and watching horror films.

Occasionally, I wonder why I’m so drawn to the macabre. What is it about H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror, a new Netflix scare-fest, or a walk through an old cemetery that sparks joy for me? Why do I want to be creeped out?

Many of us who love horror may have asked ourselves this question. It seems counterintuitive, doesn’t it? Humans crave safety, love, and comfort, yet some of us can’t resist the thrill of a scary story told in the dark.

Interestingly, the reasons why some people love horror have been studied extensively, especially now that the genre has reached mainstream popularity and become a thriving business.

A unique thrill

At its core, horror lets us explore fear in a controlled way. It’s a chance to experience dread and uncertainty while knowing, deep down, that we’re safe. And for some of us, that dance between fear and security is exhilarating.

One of the reasons we’re drawn to horror is the unique thrill it provides. Horror mentally and physically stimulates us, igniting opposing sensations: fear and excitement. We teeter between dread and exhilaration as we anticipate terrifying moments on screen or in a story.

This dual stimulation peaks when we’re most afraid; oddly enough, that’s when we feel the most alive. Biologically, horror triggers the release of adrenaline—heightening our senses, quickening our pulse, and giving us that unmistakable rush of energy. It’s a wild ride that our bodies respond to instinctively, even if our rational minds say, “It’s just a movie.”

Few of us will ever meet a Hannibal Lecter or live through a Purge-like scenario, but horror lets us safely explore the farthest reaches of human depravity.

Beyond the thrill, horror offers us a taste of the unknown. Apocalypse films, with their zombies and alien invasions, let us step into alternate realities—places we might never visit otherwise.

It’s the same reason we visit haunted houses or dare to explore abandoned buildings. There’s a sense of accomplishment in surviving these adventures, in proving to ourselves (and maybe others) that we’re bold enough to face our fears head-on. These experiences aren’t just adrenaline-fueled—they also boost our confidence and give us some serious bragging rights.

‘Protective frames’

Then there’s the deep-seated curiosity we all have about the darker side of the human mind. Few of us will ever meet a Hannibal Lecter or live through a Purge-like scenario, but horror lets us safely explore the farthest reaches of human depravity.

What would it be like to confront pure evil? To witness the worst parts of humanity without personally enduring the consequences? Horror acts as a psychological sandbox where we can observe and analyze the depths of human nature without putting ourselves in danger.

Of course, to truly enjoy horror, we need to feel safe. Researchers call this the “protective frame”—a mental buffer that lets us engage with fear while knowing we’re not at risk. There are three main types of protective frames:

We can watch terrifying scenes unfold because we know the threats are safely contained within the screen. The moment we start to believe that the monsters are creeping out of the TV, the fun is over, and panic sets in.

We remind ourselves it’s just fiction—great acting, clever effects, and makeup. This detachment lets us experience fear without being overwhelmed by it.

If we believe we can manage or overcome the danger, we’re more likely to enjoy the experience. In a haunted house, for example, we might reassure ourselves, “I can easily outrun that slow-moving zombie.”

Without these protective frames, horror becomes unbearable rather than enjoyable. This explains why some people avoid horror entirely—if they can’t maintain the mental distance, the experience becomes more traumatizing than thrilling.

Openness to experience

But why do some people love horror more than others? The answer lies partly in our personalities. Those with a high sensation-seeking trait—people who crave thrills and excitement—are likelier to seek out and enjoy horror.

Conversely, those who prefer comfort over chaos might shy away from anything spooky. The trait of “openness to experience” also plays a role. More imaginative or curious people tend to gravitate toward horror because it provides a creative, unpredictable escape from reality.

Interestingly enough, empathy also affects our enjoyment of horror. Those who feel deep empathy for others might struggle with horror films, finding it hard to watch people suffer, even when they know it’s fictional. Less empathic individuals, however, can distance themselves from the torment on-screen and revel in the thrill.

Gender and age factor in as well. Research shows that younger people are typically more drawn to horror, with men being bigger fans than women.

However, the type of horror experience we prefer may differ—women, for instance, are more likely to enjoy a horror movie with a hopeful ending where the villain is defeated. Conversely, men often relish more intense and terrifying narratives, regardless of how things unfold.

While horror may seem like pure entertainment, it actually offers a few surprising benefits.

Interestingly, our country’s economic status might also influence our taste for horror. Studies reveal that people in wealthier countries with a higher GDP per capita are more likely to consume horror movies. This may be because having more financial security strengthens the protective frame we need to enjoy horror, while those in less economically stable environments may feel too vulnerable to embrace fictional fears.

The benefits of horror

And while horror may seem like pure entertainment, it actually offers a few surprising benefits.

Watching a horror movie on a date might spark more than fear—it can ignite romance. Sharing the heightened emotions of a scary experience can create a bond, making you feel closer to your partner.

Horror is also a great way to connect with friends and family. Experiencing fear together triggers the release of oxytocin, a hormone that promotes closeness and trust. So, if you’re looking for a bonding activity, maybe consider a horror movie night.

After the terror subsides and the villain is vanquished, our brains release endorphins—a natural reward for surviving the ordeal. After a scare, these “feel-good” chemicals leave us feeling relaxed, even euphoric.

Horror isn’t just about facing our fears—it’s about the rush, the relief, and the connections we make along the way. Whether we’re bonding with loved ones or simply basking in the glow of survival, there’s something undeniably captivating about dancing with darkness.

Leave a comment